| SMHRIC |

| March 27, 2023 |

| New York |

|

|

|

|

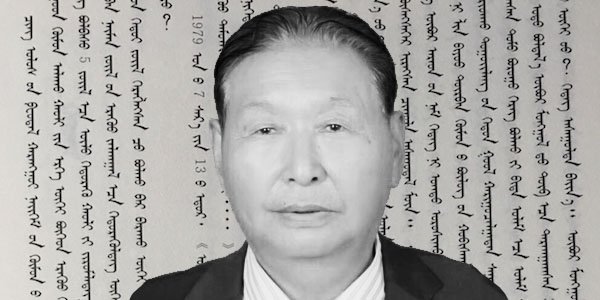

After being sentenced to two years prison term followed by indefinite surveillance, Southern Mongolian writer Lhamjab Borjigin escaped China and arrived in the independent country of Mongolia. |

The following is an English translation of Southern Mongolian dissident writer Mr. Lhamjab Borjigin's testimony given to the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center on March 26, 2023. After being sentenced to two years prison term followed by indefinite surveillance, recently Lhamjab Borjigin managed to escape China and came to the independent country of Mongolia (English translation by SMHRIC):

It was nice reconnecting with you. In Southern Mongolia, people like myself — branded as undesirable and blacklisted as reactionary — are under the authorities’ strict control, monitored and followed around the clock. We must show up wherever and whenever they summon us, and we must report in several times a day. No matter where we go, we are followed.

All Southern Mongolians are treated as targets for cleansing and extermination. What they [the Chinese authorities] want is our land and territory. As a people, we are considered nonexistent.

I am not allowed to meet with others like me. We spend our days, months and years under these restrictions — and even stricter policies imposed on us during the COVID-19 lockdown.

During the lockdown, a total of four doses of the vaccine were forced on each and every one of us. Realizing its ineffectiveness, many refused to receive the fourth round of inoculation. After a couple of years of vaccination, people realized the Chinese vaccine does not work at all. Despite this resistance, the authorities achieved their vaccination goal through a variety of means. For example, in Sunid Right Banner, the government issued a sack of flour or a bottle of milk to elderly citizens who agreed to being vaccinated. I have heard that in other locations, inoculated citizens were given 500 yuan.

As an 80-year-old man, I am against the Chinese vaccine, which has been proven ineffective over time, considering the government’s protracted period of vaccine administration. In fact, the negative effects of the vaccine are well known — but discussion of these side-effects is not allowed. It is a fact that many people have died as a result of the vaccine. Discussion of these deaths is also strictly forbidden. We must attribute these casualties to natural causes. It is said that those who have discussed vaccine deaths have been criminalized.

In cities, dispatchers in white hazmat suits walked door to door, forcefully vaccinating residents. In some cases, they even broke into people’s homes in order to administer the vaccine. I, however, have never allowed them inside my home. I recall on several occasions they came to my place of residence with an army of police officers and security personnel. I told them that diseases are treated by doctors, not by the police. I said that my body was given to me by my parents — not by the party, nor the government. I have the right to decide what to do and what not to do with my body.

I also told them that with this vaccine they were not trying to save my life but were in fact attempting to take it from me. In this manner, I categorically rejected the vaccination, yet I still haven’t contracted COVID-19, thanks to my natural immunity. Some of my acquaintances who were vaccinated either died or fell victim to worsening conditions.

During the language protest, many teachers died. Those parents who refused to send their children to school were either removed from their positions or fired from their jobs. Many of their family members and relatives were implicated as well. Many Mongolians lost their lives. Some Mongolian officials who supported the protest have mysteriously died or disappeared. Again, it is a taboo to talk about these cases. This is a form of genocide, executed by the Chinese in Southern Mongolia under the guise of protecting citizens from COVID-19.

Similarly, under the pretext of the COVID lockdown, roads and highways were often blocked and sealed. Having obstructed citizens’ mobility, the authorities then quietly moved their police and paramilitary forces into Mongolian areas — fully equipped with heavy machinery — under the cover of darkness, and with the goal of tightening surveillance.

And there was much to surveil. We Mongolians are prohibited from communicating with outsiders — especially foreigners. Those who broke these rules were searched, arrested, detained and jailed. Their phones were confiscated, hacked and analyzed thoroughly. After all personal information and communication records were accessed and copied, some devices, but not all, were returned to their owners. The so-called “rule-breakers” were warned about who they were allowed to communicate with, as well as those who were strictly prohibited. They are monitored and followed around the clock. For instance, the entire city of Shiliin-hot was patrolled by heavily armed police and SWAT teams in black vehicles who monitored residents’ every single move. And our literal movement was restricted as well. They [the authorities] even tried to confiscate my passport. I was able to avoid surrendering my passport by telling them that I had misplaced it. In lieu of relinquishing my passport and therefore my freedom to travel, I was ordered to check in at the local police station twice a day to report my status and sign a statement of compliance.

When COVID restrictions relaxed slightly, I managed to escape and come to Mongolia with the help of friends. Like a wild animal, I broke through the shackles and ran for my freedom. I do not want to go back, only to be shackled again. It is my dream to live in peace and to enjoy my basic human rights in a free country, for the few remaining years of my life. My other goal is to publish my books here in Mongolia.

Generally speaking, Southern Mongolia is under Chinese control. At the regional level to the lowest level of villages, the Chinese dominate everything, all the way from high-level government offices to our schools. In schools, including kindergarten classes, all Mongolian teachers have been replaced by Chinese instructors hailing from the interior provinces of China. For example, in Shiliin-hot, the Shiliin-gol League Mongolian High School (established in the 1930s) has been converted to the No.3 Chinese High School. The Mongolian teachers who taught there are now unemployed.

Moreover, Mongolian textbooks and other publications have been removed from bookstores and libraries. Some teachers managed to keep a few Mongolian books by hiding them in nooks and crannies. Even the most sacred book — Secret History of Mongolia — was confiscated and destroyed. Those books that escaped the search nevertheless cannot be shared with the public.

Mongolian students have not learned anything in the past two years, not only because of the deteriorating educational environment, but because of the early dismissal schedule, ostensibly necessitated by COVID-related restrictions. Those students who were forcibly returned to their homes effectively spread COVID-19 to their family members and rural communities.

For the time being, I live with my friend here in Ulaanbaatar. As there is no possible way for my books to be published in Southern Mongolia, it is my goal to publish them here in Mongolia.

Having enjoyed only a handful of days of freedom here, I can’t begin to describe how precious freedom is. Let me be frank. I do not want to go back. I do not want to lose the freedom that I have dreamed of for so long. I know I do not have a great many years ahead; still, I would like to live in freedom and die in peace.

If I did return to China, I would be severely punished, if not killed, for escaping to Mongolia without the government’s approval. As mentioned earlier, before my departure I had been placed under indefinite surveillance without any personal freedoms. The authorities must have been furious about my escape. As a result, it is extremely risky for me to go back. On the other hand, I really want to see, touch and feel this hard-won freedom.

In Southern Mongolia, this denial of freedom was only exacerbated by charges brought against me by the Chinese authorities. I was sentenced by the court of Shiliion-hot to one year in prison and one year serving outside prison. I completed the full sentence — but completion of my full sentence did not guarantee my full freedom. I still had to regularly report to the local Public Security Bureau. They decided where I was allowed to go and where I could not go, and who I was allowed to meet and who I could not. My residence was full of surveillance cameras, watching my every single move, like the Monkey King’s golden hoop remotely controlling the entirety of my daily life.

Having lived through the turmoil sustained by my people, I would be happy to share my experience with the outside world as a victim, survivor and witness. I abide by this simple principle: for the cause of my people, for justice and righteousness, I do not hesitate to stand up and tell the truth.

As you know, publishing books in the Mongolian language in Southern Mongolia has been completely outlawed. Even government and party propaganda are no longer published in Mongolian. Having worked on my books for years, I took the risky path to Mongolia armed with the hope of publishing them here and bequeathing them for posterity. Through my books, future generations will understand what our nation has endured, and how our people fought for survival.

The first book I am planning to publish is about Mongolian history, mainly focusing on the personal lives and achievements of more than 30 Mongolian Khans, in chronological order. The estimated word count is roughly 100,000 after editing.

The second book is entitled The Record No. 1981 and focuses on the Mongolian Students’ Movement of 1981. The first draft is about 200,000 words.

The third book is a historical account of the Chinese Communist Party’s occupation of Southern Mongolia, primarily focusing on when and how the Chinese Communist Party took control of the Shiliin-gol region, how they occupied Mongolian land and territories, how they confiscated and destroyed Mongolian properties, the nature of the political movements they launched, and how they carried out mass killings and other atrocities. The estimated word count of this book is 150,000.

These three books could be published in relatively short order, as first drafts are already complete. In addition to these manuscripts, I have also brought with me a fair amount of first-hand materials that will require some sorting and time and effort prior to publication.

These are my plans — should I be lucky enough to live a few more years in peace without being followed, monitored and questioned, until being called by Karl Marx to join him in heaven.For more information on the case of Lhamjab Borjigin, please visit here:

http://smhric.org/news_651.htm

https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/mongolian-historian-07232018123931.html

https://pen.org/press-release/lhamjab-borjigin-historical-inquiry-on-trial/

Beyond

Great Walls: Environment, Identity, and Development on the Chinese

Grasslands of Inner Mongolia

Beyond

Great Walls: Environment, Identity, and Development on the Chinese

Grasslands of Inner Mongolia China's

Pastoral Region: Sheep and Wool, Minority Nationalities, Rangeland

Degradation and Sustainable Development

China's

Pastoral Region: Sheep and Wool, Minority Nationalities, Rangeland

Degradation and Sustainable Development The

Ordos Plateau of China: An Endangered Environment (Unu Studies on

Critical Environmental Regions)

The

Ordos Plateau of China: An Endangered Environment (Unu Studies on

Critical Environmental Regions)